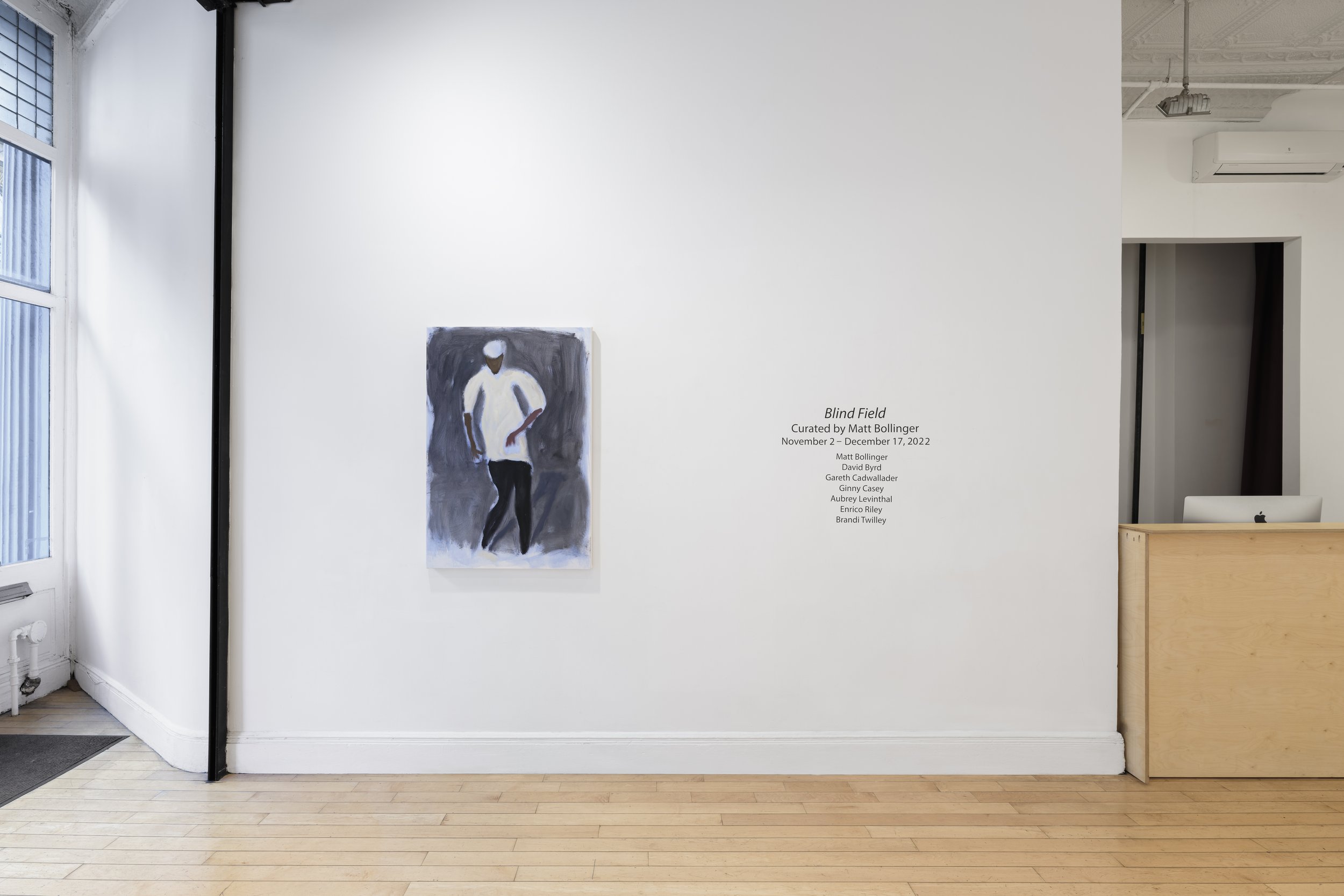

Blind Field Curated by Matt Bollinger

Matt Bollinger, David Byrd, Gareth Cadwallader, Ginny Casey, Aubrey Levinthal, Enrico Riley and Brandi Twilley.

Exhibition Dates: November 2 - December 17, 2022

Opening: Wednesday, November 2 @ 6PM-8PM

39 White Street, Tribeca

1969 Gallery presents Blind Field, including works by Matt Bollinger, David Byrd, Gareth Cadwallader, Ginny Casey, Aubrey Levinthal, Enrico Riley and Brandi Twilley.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes mentions something called the blind field. This term refers to the suspension I experience when someone in a film walks off frame and I think they still move in a room or wherever, specifically the continuation of the fictional space projected before me, as opposed to a sound stage somewhere. The idea has lingered in my head for more than 15 years since I first read it and has morphed a bit to make it applicable to painting. The blind field creates a double inside for a painting. There is the painterly or pictorial space, but then a side door through which the imagination can wander. The painting is a fixed aperture adjacent to the blind field, just as the viewer is adjacent to the painting. But the blind field only appears to be just beyond the space described by the painting, when in fact, it is in the viewer’s mind.

In Brandi Twilley’s paintings, images of Lake Thunderbird in Oklahoma (the artist’s home state) and Brighton Beach fill cartoon thought bubbles. These image-ideas float over an empty studio space—the Brooklyn studio where Twilley formerly squatted and worked. It is as though a dream of a large body of water replaced the misery of confinement. At the same time, the image of escape blocks the view of the present moment. In Lake Thunderbird’s Red Water, a cadmium glow seeps up from beneath the ideal blue water. It is like an algae bloom, while at the same time, the blue light spills across the concrete floor in an excitement of painterly moves. Twilley seems to suggest that art allows for the space for opposites not just to coexist but to cross-contaminate.

In Enrico Riley’s paintings, gestural marks create a harmony between his movements in the process of making and those of the Black dancers he depicts. Riley essentializes the figures to marks, the minimum information for identification. At the same time, he complicates his surfaces through his use of color. Layering black over blue before adding subtle shadows, he pushes his color fields back into deeper space. Near and far at once, his paint and dancers move. Stepping and swaying, his figures and his brushwork suggest a celebratory energy while his titles, Protective Gesture, Force Field, and Together; Impervious point to a danger that these social moves—dancing, being together—protect against. These dancers and Riley’s brush strokes give the sense that creative acts help create security through community. The Black men and women in these paintings dance together but also with you when you look at them.

Aubrey Levinthal’s painting, Black Dress, creates tension from compression. First the figure, presumably a self-portrait, looks out of the image from behind the black dress, starkly delineated as a shape, which connects with the like-colored fan that it overlaps. The lavender mirror frame, offset from the edge of the painting, creates a picture within a picture while the body meant to wear the dress vanishes aside from face, hands, and feet. The dress fluctuates between a flat shape and a deep space, by turns erasing the body and opening up the core to great depth. Levinthal’s black dress creates a disruption in the everyday, a blind field that contains space for a self beyond what clothing can convey.

Like Levinthal, Gareth Cadwallader’s works depict commonplace events while suggesting something out of the ordinary. His paintings, View from Sailor Girl III and View from Sailor Girl IV, are pendants to a work depicting the eponymous sailor girl. Here they become moments of contemplation. Their diminutive size gives them a hyper-focused quality. I peer into the spaces, each an inversion of the other. In one, the lemon is a luminous yellow shape on the cool table cloth, while in the other, the lemon appears shadowed with the lemon yellow (and lemon-sized) moon hovering, mirrored overhead. Cadwallader’s work suggests that simple observation is a visionary act. Colors, shapes, and curvilinear forms ripple to the surface of a deceptively everyday scene. The blind field sits beneath the illusion, creating an analogous ripple in my mind.

In Dwight and Dwayne, I have painted two figures: a young, white man and a preschooler in a Cars top and Pull-ups. They sit on the ground in a yard surrounded by a fence. Both hold dandelions, gestures that mirror one another. I have been preoccupied with families and the relationships between fathers and sons, big brothers and much younger siblings. The dynamics of masculine care and neglect (problem fathers and protective siblings) has driven many of my recent paintings. I imagine Dwight and Dwayne are brothers, killing time in the backyard although it is unclear whether they are avoiding something or waiting for something to happen.

Ginny Casey’s Through the Page shows two snake-like creatures boring through a book that has lodged around their necks, leaving them face to face. The wooden floor (there is no furniture) extends to the mottled blue wall, surreally far, in which there is a doorway cut irregularly through the wall. This is a mental space where Casey’s orthographic understanding of her world allows her to play out a scene of the dramatic and destructive tension between two very similar beings. This could be a disagreement between friends or sisters. Intricately and intimately, Casey applies paint with feathered strokes across the surface of the painting. As a result, time seems to slow to a subtle flicker as with an old film played back at half speed.

David Byrd (1926 - 2013) spent much of his working life as an orderly at a VA hospital in Montrose, NY. During that time and after his retirement in 1988, he painted images, primarily from memory, of the patients in the psychiatric ward at the hospital. In Man Showering, a figure ostensibly covers his body with soap in the communal baths in Montrose, but the suds and Byrd’s strokes of thin oil merge. As with Riley’s paintings, there is empathy between the artist’s gesture and the act depicted. The man’s arm bends unnaturally as he soaps his underarm. His naked, pale flesh melds with lumps of soapsuds, staying close to the wall behind. Byrd painted on a gray priming and this gives his oils an overcast lighting. At the bottom of the painting, the man’s feet extend down onto this primed but otherwise unpainted ground. In Outer World, Byrd covers the surface with countless small marks and flecks of cross hatching in contrasting but muted color. He leaves just two moments of more solid shape: the white window that the patient looks out of and the V of light where the outside light enters, split by the man’s statue-like face.

The paintings in this show all catalyze something in my head, pick up the props and actors from my experience and relate them to what I am seeing: the time I danced in a parade with my daughter or found worm holes in an old, used book. Perhaps all art does this in its way, but the blind field makes a special collaborative space and takes the flat plane and bends, bows, or extends it. Memory and narrative work with paint and imagery to grow a world in my mind. These paintings are particularly generous, giving more than I see, evoking my experiences, but then transforming them into their own language so I can see through someone else’s eyes.

—Matt Bolling

Curator:

Matt Bolinger (B. 1980, Kansas City, MO) lives and works in N.Y. State. Bollinger was awarded a BFA from Kansas City Art Institute (2003) and an MFA from Rhode Island School of Art and Design (2007). As an American artist, Bollinger’s drawings, paintings and stop motion animations, consciously grapple with the ‘veritas’, or otherwise of the American dream, and captures the zeitgeist of its dystopian dark side. In a manner of painting that consciously acknowledges its cultural roots grounded within American modernism, from Diebenkorn to Hopper, Bollinger thoughtfully and tenderly depicts the everyday social derelictions, the small socio-economic diminishments, but human gains and bonds, generated by ravages of the post-analogue, Anthropocene epoch in the shared experience of innumerate locations across the contemporary world. Matt Bollinger’s work has featured in recent museum exhibitions; The Westmoreland Museum of American Art, Greensburg, Pennsylvania (2022); South Bend Museum of Art, Indiana (2020); Phillips Museum, Lancaster, Pennsylvania (2018); Nerman Museum, Overland Park, Kansas (2016); Musee d’art Moderne et Contemporain, Saint-Etienne (2016). Other solo exhibitions include, Zürcher Gallery, New York and Paris, M+B, Los Angeles (2020). Matt Bollinger held his first London solo exhibition Collective Conscious with mother’s tankstation in 2021 and in September 2022 will present his first Dublin solo exhibition Off Peak.

For inquiries, please contact:

Quang Bao | e: quang@1969gallery.com

About 1969 Gallery

Founded in September 2016, 1969 is a contemporary art gallery, with two gallery spaces in Manhattan’s Lower East Side and Tribeca neighborhoods. Through solo / group / external exhibitions and art fair presentations, the Gallery has cultivated the careers of its represented artists and a broader community of artists primarily devoted to painting.

Follow 1969 Gallery on Instagram via @1969gallery.